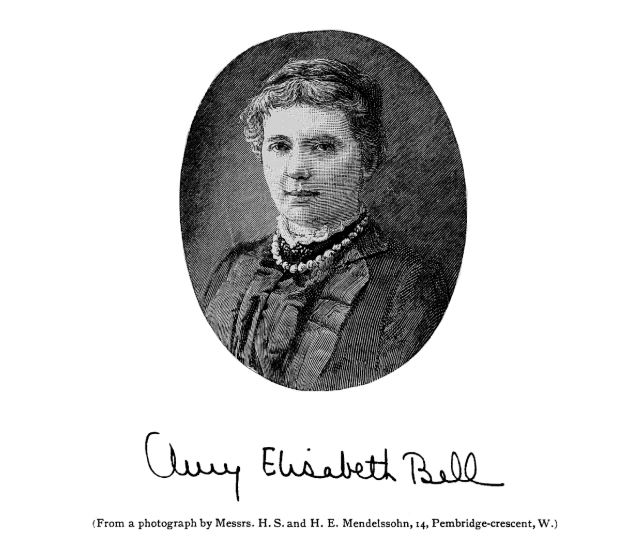

Amy E Bell holds the distinction of being the first British woman stockbroker, at least as far as the publication Common Cause was aware when they published her obituary, and indeed there is no record of anyone having held that position earlier in the UK. The USA had Victoria Woodhull and her sister Tennessee Clafin, who had established a Wall Street Brokerage firm in 1870, but Amy was the first in the UK. However, she was never admitted to the London Stock Exchange – although there was no specific rule banning women from entering, new members had to be voted upon and anyone female was immediately blocked by the old boys network until six women broke through in 1973 – Muriel Wood, Susan Shaw, Hilary Root, Anthea Gaukroger, Audrey Geddes, Elisabeth Rivers-Bulkeley.

Other regional exchanges – in places like Birmingham, Liverpool and Manchester – had admitted women a bit earlier, but it was the 1973 merger with London that brought on the change. However, when Amy was practicing, during the 1880s and 1890s, the landscape of the financial world was very different, and this change nearly 100 years in the future.

A close friend, Edith C Wilson, writing in Common Cause a week after the obituary, says that Amy’s health meant that she had no wish to challenge the establishment and attempt to get into the LSE, but instead preferred to work outside the institution like many provincial brokers of the age – getting a member on the inside of the exchange to fulfil any necessary jobs for her. So, she established her business in Grays Inn, near to the LSE hub.

But how did she get to be a stockbroker in her era in the first place? The answer lies in her early years and level of education.

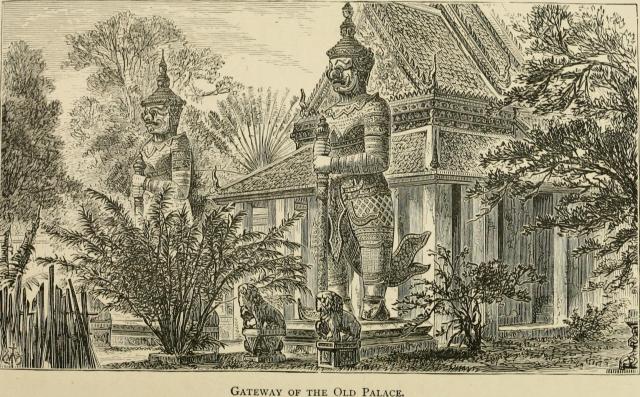

She was orphaned at around six months old. She’d been born in Bangkok, then in Siam, now in Thailand, in February 1859. Her father was Charles Bell, who had been appointed to the position of Vice Consul of Great Britain to Siam in 1857. Before this, Siam had been independent of colonial interests in the region, but the Bowring treaty – brokered by John Bowring, the British Governor of Hong Kong at the time – established some close links with the King of Siam and the British government at the time, and it was felt by Secretary for Foreign Affairs George Villiers, 4th Earl of Clarendon, that diplomacy should be established in the Kingdom and Charles was appointed.

He married Charlotte Erskine Goodeve in November 1857 in Singapore, and Amy was born over a year later. Little information survives of their life in Bangkok. A letter from King Mongkut to John Bowring makes mention that Charles is living in a house at the frontier part of the palace of his younger brother Krom Hluang Wongsahdi Rajsnidh (another of the 73 children of Mongkut’s father Rama II). He says that, while Amy’s father’s command of the Siamese language is now extensive, he has little to do and lives quite idly – which speaks of a relaxed and privileged life on the part of Amy’s parents, and a newspaper report of the time says that the consulate was on the river, and served elaborate dinners. Another report of the time says that Charles was involved in trying to get Siam to adopt silver coinage.

As to exactly what happened to Charlotte and Charles, the record is unclear. They died a week apart, in early September 1859, in Bangkok. There is no unrest known in the area at the time, so it seems likely that both were ill, and succumbed one after the other. They were 27 and 28 respectively and were buried in Bangkok Protestant Cemetery. Charlotte became a widow for the last week of her life, and her will transferred care of baby Amy – along with £4,000 – to her brother John Goodeve back in England.

John was studying medicine at Queen’s College, Cambridge, at this time, so it wasn’t to his house that Amy was brought. Her grandfather, Doctor William James Goodeve, would have been perhaps the next option – but he had recently buried his third wife and had several small children of his own, so it was to her great uncle Dr Henry Hurry Goodeve’s house in Bristol that Amy was taken by her nursemaid from Bangkok.

Henry Goodeve was married to Isabella, without any children, and looked after various parent-less members of his and his wife’s family, so his house Cook’s Folly, overlooking the Avon Gorge just outside Bristol, was perhaps the obvious place for baby Amy. They had her christened, in March of 1860, and cared for her alongside relatives and a vast houseful of staff. They had previously adopted Isabella’s nephew, another Henry.

This placement for baby Amy turned out to be a good call, as her grandfather died before she was 3. Amy continued to live with Henry and Isabella and their household, and was nurtured and educated as if she was their own child. Henry had served as a doctor in the British army in Bengal, and had been involved in both training Indian doctors and caring for children, as well as furthering medical research. He published a first aid book, called Hints on Children in India, that went through many editions. He had also been hit by a stray bullet on a tiger shoot, which shattered one side of his jaw and marked him for the rest of his life. He also later worked as a doctor in the Crimean War.

On retirement he became a Justice of the Peace, a tax commissioner, and deputy-lieutenant for Gloucestershire, and sat on the board of the local poor law executive. He was also president of the Bristol and Clifton Society in Aid of Boarding Out Union Orphans and Deserted Children, and was a passionate advocate for this. While today we might see removing children from their families as horrific, and rightly so, the Victorians truly believed that they were doing the best for the children and giving them a chance for a better life.

Henry Hurry Ives Goodeve

Her great aunt Isabella died in 1870, when she was around 11. Great Uncle Henry reputedly made Amy his companion in all of his interests, so presumably would have included her in visits and discussions around his businesses and duties. She began reading The Times newspaper daily, studying the content carefully, under his guidance. They also employed a Swiss governess, Sophie Girard, under whose guidance Amy became a competent linguist. She was exceedingly well read, and a lover of poetry.

Her interest in money, stocks and shares reputedly began in early childhood. Her story was that, as a small child, an elderly gentleman visitor while reading The Times attempted to shoo her away to her own lessons. Amy apparently told him that “What’s your lessons is my play,” as she believed it great fun to watch the rise and fall of stocks on the money market.

Later on, as detailed in Jane Duffus’s fabulous book The Women Who Built Bristol 1184-2018, Amy was one of the earliest entrants to Bristol University to study. Bristol University admitted women from opening in 1876, when she was around 17 (university entry was often earlier then than today), and studied with several other women.

After this, she won a Goldsmiths scholarship to Newnham College Cambridge, the first purely female institution there, and continued her studies. Principal at this college at the time was Anne Jemima Clough, another pioneering female academic.

However, Amy’s health was said to be precarious – perhaps affected by the illness that had taken her parents – so a friend later commented that for this reason her studies at both Bristol and Cambridge were necessarily brief. The 1881 census has her at home with her guardian, her relatives and her governess in Bristol, 22 years old and unmarried.

When her great uncle died in 1884, Amy declared her intention to become a stockbroker. It was widely believed at the time that she had somehow inherited the stockbroking business from a relative, but this was not the case. It was her idea and dream. Using money she had inherited, she initially appears to have set up in Bristol, but in 1888 moved her business to London.

Many of her clients were women of modest means, with a little to invest – the sort of amount that the top stockbrokers of the day would have considered piffling and really below their interest. But Amy knew that wisely invested smaller amounts of money could make all the difference for women’s survival on private means. In an era where men were the main earners, and if you lost your breadwinner you would inherit what he had left, judicious investing could pay dividends and keep a household going.

“You need to begin afresh every day,” says Miss Bell, speaking of the difficulties of her business. By this expression I take her to mean that the work cannot be performed in installments, as a man writes a book, with a chapter yesterday and another to-day. “And then,” she continues, “you must do everything yourself. You must read a great deal – books of history and political economy economy chiefly – but the newspapers continually. Keep an eye on the colonies and these newly explored African territories, did you say? Yes, indeed, and not one eye but a dozen if you had them! The chief qualifications for a successful stockbroker are, in my opinion, a keen interest in the world’s affairs and sympathy with individuals. … By sympathy with individuals I mean the power of understanding your client’s position. If, for instance, a woman writes to me and says she is old and a widow, that her family are comfortably settled in life, and that she wishes to make sufficient provision for the rest of her days, I know pretty well what kind of investment would suit her best. But if she gives me none of these personal details, I may not succeed in pleasing her half as well.”

From Professional Women upon their Professions, by Margaret Bateson, 1895.

Although she did have some male clients, most of her customers were women. Her comment was “one of the pleasantest features about my work is the number of interested, able and cultured women with whom I have made acquaintance.”

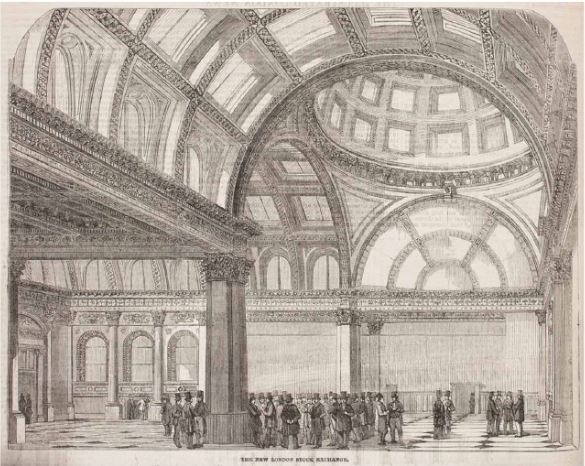

As we said before, the London Stock Exchange, because of its membership, would not allow women stockbrokers to set foot on the floor. Therefore, Amy set up the office just outside Capel Court, in Grays Inn, and operated from there. Any formal dealings with the LSE that she needed were dealt with by male members. She also had a female clerk to help her out with the work. Newspapers wrote about her and her work, but she never felt the need to advertise her services – relying on word of mouth and reputation.

Inside the LSE at the time

She doesn’t appear on the 1891 census – she was known for a love of travel, so it’s possible that she was abroad when it was taken – but in 1901 she is still in Grays Inn with her female housekeeper, who must also have been a companion, and calls herself a stockbroker agent.

At some point after this, however, her health forced her to give up work. She then lived off the proceeds of her work and devoted herself to her friends. She was known to have made a great many during her time as a stockbroker, and – although not declared as such on the 1911 census – taken interest in women’s suffrage. The 1911 census finds her in a hotel in Bloomsbury, as a guest, with a lady’s companion. Whether this is a hint towards her sexuality is unclear, but it is known that she never married. Either way, marriage would have forced her to give up work, by the propriety of the day, and it is clear that work was a considerable passion for her.

“I want,” she says, “to make women understand their money matters and take a pleasure in dealing with them. After all, is money such a sordid consideration? May it not make all the difference to a hard-working woman when she reaches middle life whether she has or has not those few hundreds?… Many women are quite astonished when I explain business details to them, and ask “But is that really all?” So many women, you see, are not allowed to have the command of their capital. But in this, as in other ways, I rejoice to see that women are daily becoming more independent.”

Margaret Bateson, 1895.

It’s unknown what she did during the First World War – reports are that she spent time living with various friends. And it was at the home of one of these friends that she died, in March of 1920, after a brief attack of influenza which brought on heart failure. This friend was Maude Ashurst Biggs, a novelist and translator with suffrage sympathies, who lived in South Hampstead.

Common Cause, the newspaper of women’s suffrage, published an glowing obituary, which her close friend added to in the following edition:

“She was an admirable pioneer, obtaining recognition by sheer force of knowledge and ability, with no ostentation or eccentricity. One great secret of her success was her happy art of turning clients into personal friends. She humanised her profession, and was happy in leaving an open path to her successors.”

Edith C Wilson, writing in Common Cause, March 1920

Pingback: “How do you find your stories?” – The Women Who Made Me