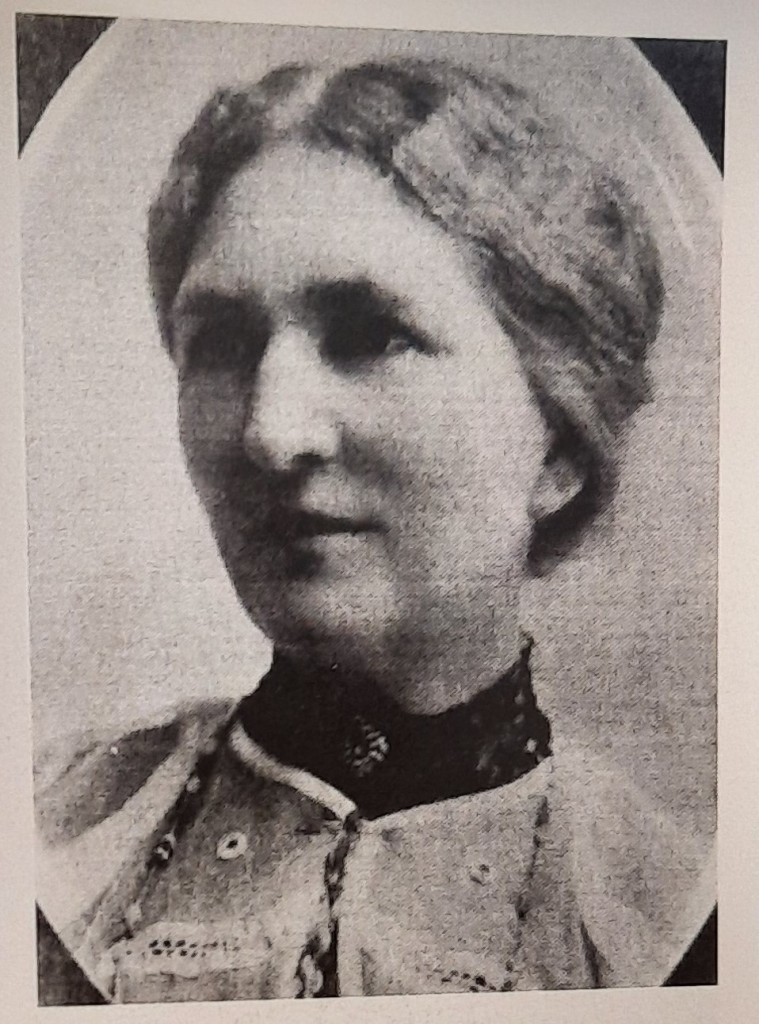

Musical prodigy Clara excelled on the piano and as a vocalist, and was entertaining on the concert platform in fashionable mid-19th century Bath by the age of nine and soon gracing stages in London and the provinces. As a young woman though, she had tired of the attention, so eloped with her sweetheart Joseph – another fine musician, but alas not so fine at business ventures, so her musical talents earned her family’s living in possibly the most genteel way possible.

She’d been born in 1844 in Widcombe, Bath, but for some reason her parents Major John Henry and Emily Diana MacFarlane (née Cottle) had opted to have her baptised at Temple Church in Bristol a couple of years later. This may have been on account of them not actually being married at the time, though they did sort that out by 1854. Her father called himself a professor of the pianoforte, sometimes a professor of music, but at this sort of time there was very little regulation for these sorts of qualification claims and he most likely took his professorship from the fact that he played well enough to be able to teach others. His father before him had been a banker, and he’d been brought up in London, so he had the means and background to be able to study music seriously.

Clara was her parents’ oldest child, and was followed by two sisters – Kate and Marion – and later two brothers, Walter and Alexander. Marion died at about 10 months old, but the rest of her siblings survived. Her widowed paternal grandmother lived close by while she was growing up, and taught children in an infants’ school, while her father took on piano pupils.

Her first reported performance was in Corsham, Wiltshire, just after Christmas in 1855, at a vocal and instrumental concert directed by her father. She was purported to be nine years old, but in reality had probably recently turned ten. The Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette said:

“The performance of Miss Clara Macfarlane, the talented juvenile pianiste and vocalist, elicited great applause from the audience, who were surprised at the powers of so young a performer.”

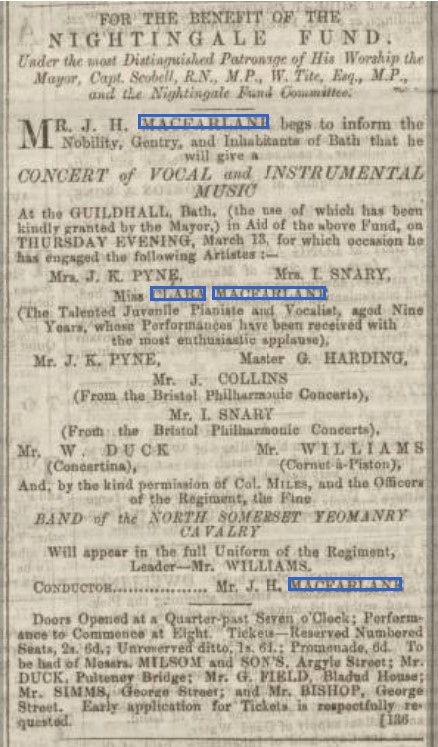

In March the following year she was part of a benefit concert for the Nightingale Fund at the Guildhall in Bath, where her father had invited the nobility, gentry and inhabitants of the city to hear her play alongside musicians from the Bristol Philharmonic Concerts and the Band of the North Somerset Yeomanry Cavalry in full uniform. The Nightingale Fund, though officially funded in 1857, was earlier than that part of fundraising undertaken for Florence Nightingale towards the end of the Crimean War.

Clara’s father again conducted, and she was again supposed to be only nine years old. The newspapers, in this case London’s Morning Herald, were again gushing in their praise.

“A very interesting portion of the entertainment consisted of the pianoforte performances of Miss Clara Macfarlane, a child only nine years of age. The audience were most agreeably surprised at the powers of execution and the musical genius which she manifested. She performed, in an admirable manner, two fantasias, one of airs from L’Elisir, and the other from Lucrecia Borgia. We have no hesitation in predicting for this child much future fame.”

Subsequent prominent concerts, of which there are several, make no mention of her age – being in single digits was clearly a selling point, and once she’d passed that it wasn’t remarked upon. Instead, she’s referred to as a “juvenile pianiste”. Press reviews are no less glowing, however old she was. There were performances at the Bath Guildhall, the Cardiff Assembly Rooms, the New Hall (now the Neeld Hall) in Chippenham and the Court Hall in Trowbridge before she was twelve years old.

The 1861 census found the family living at Nile Street in Bath, with her father describing himself as an organist – so, in addition to teaching the piano, arranging and conducting concerts, and playing the cornet à pistons for solos, as several concert reviews report, he also had a hand in church music at that time. Clara was fourteen and described as a scholar, so was continuing her education beyond the minimum – though her studies could just have been musical.

As the 1860s wound on, reports of Clara’s musical prowess continued, although her young age is mentioned less and less in reports as her abilities became slightly remarkable in the context of her peers. Her father around now owned a music shop on Pultney Bridge in Bath, selling instruments and sheet music. There were notable performances in Midsomer Norton and Bristol, and she was often appearing alongside her father’s work. Away from the reported concerts, she was probably in a world of choral societies, private appearances, endless rehearsals and constant practice, and after spending so much of her childhood as her father’s display, this may have been wearing a little thin. Her mother also seems to have died at some point in the 1860s, as by 1871 her father was calling himself a widower. An exact record for this has proved illusive, however.

Around the concert circuits, Clara had met singer Joseph Goold, who hailed from Corsham – just a few miles east of Bath. He was one of the sons of a prosperous tan-yard and quarry owner in the tiny Wiltshire town, and as such would have been on a similar class footing to Clara. He also had a beautiful bass singing voice. The family story goes that Joseph approached Major John Henry Macfarlane and asked for her hand in marriage, which was refused in no uncertain terms. Her marriage would effectively end her performing career – in respectable circles at this time, and even more so as the 19th century wore on, married women did not publicly appear on concert stages, no matter how talented they were. Their talents went into their new family, and they could perform privately amongst friends, but a stage like those Clara frequented was frowned upon.

Either her love for Joseph was strong, or she had deep dissatisfaction with her life as it was, but taking matters into their own hands, Clara one day in early 1864 told her family that she was off to visit her dress maker… and instead eloped with Joseph in Corsham. She would have been around 20, and as such technically too young to marry without a parents’ permission or license, but many young couples at this time fudged their ages slightly, and it was a common practice in the church and registry offices to not probe too hard.

Family stories say that the newly-wed couple’s grand plan was to set up a book shop in Swindon to support their new family. Swindon at this time was still in two parts – Old Swindon (now known as Old Town) at the top of the hill, and New Swindon which was growing around the railway works on the flat land beneath. New Swindon was booming, and it may have seemed an exciting prospect to found a new business. In reality, though they were living in the area for a while, this venture seems to have not lasted very long at all. Clara had her first child, daughter Daisy, in the November of the following year, who was registered in Highworth – a smaller community just to the north – and she was followed eighteen months later by a second daughter named Kate.

A few months after Daisy’ birth there is a mention of one of the final public performances attributed to Clara in the newspapers. She and Joseph appeared together with other members of Corsham musical societies at an annual soiree in April 1866, where she sang and played piano alongside him. This event was repeated in 1868. This may have been just private enough for Clara to appear, as there are other married women on the bill, and they probably needed the money.

By the time her third child – Edith – arrived, in the summer of 1869, Clara and Joseph had made a big change and undertaken a move to Nottingham. This was about 150 miles away from Corsham. She’s mentioned as having done a tiny bit of performing, bumping along at community entertainments, in Nottingham in October of that year.

They’d gone to Nottingham so that Joseph could set himself up as a soda water manufacturer. This industry was experiencing a bit of a boom, as the Victorian temperance movement was growing. Carbonated drinks, like sparking water and ginger beer, had a similar sensation in the mouth as a fermented beverage, but none of the pesky alcohol. They were therefore promoted as a more wholesome alternative, particularly around some non-conformist church movements. Joseph, who called himself an inventor, and in 1871 was employing three men and a woman at his plant near Mansfield Grove in Nottingham, could have made it big with this new business venture.

He didn’t. At some point in the 1870s the manufactory went south. Clara had another baby, Alice Bertha, in July 1871, bringing their quota of small children to four. His business, though it’s unclear exactly when it failed, was not mentioned in the Post Office directory of Nottingham published in 1876.

Instead, to keep their family afloat, they appear to have begun to rely on Clara’s talents as a pianist, which were relatively unknown in Nottingham before this time. Despite the socially uncomfortable issues around married women performing, she took to the stage at an entertainment in April 1872, where the Nottingham Journal reported:

“We ought not, perhaps, to conclude without stating that Mrs Goold, who, we believe, appeared last night for the first time in public as a pianist, in Nottingham, acquitted herself with remarkable efficiency at her instrument in the very difficult music she had to play. We have reason to know that many at the concert will be glad to have an opportunity of hearing her again.”

She was able to build upon this exposure, and by 1881 they’d had five more children – Ernest, Amy, Irene, Stanley and Vivian – had downsized their accommodation quite considerably, and she had established herself as a teacher of music on the Nottingham scene. Her brother Walter also went to Nottingham and worked as a music teacher. On the 1881 census her husband Joseph described himself as a druggist (which was possibly related to his soda water interests) and an author of scientific works. Throughout the 1880s he was contributing to discussions on the construction and pitch of scales in musical publications of the day, and doing work on harmonics and vibrations – which had a basis in maths and physics.

However scholarly and inventive the work, it did not pay the family’s bills. So, Joseph became a book keeper and a clerk, and Clara continued to take in many piano pupils. They moved closer to the newly-opened university college in the city, possibly so Joseph could undertake his research closer to other deep thinkers. It appears that he also occasionally worked as a piano tuner, which would have influenced his research on pitch and harmonics.

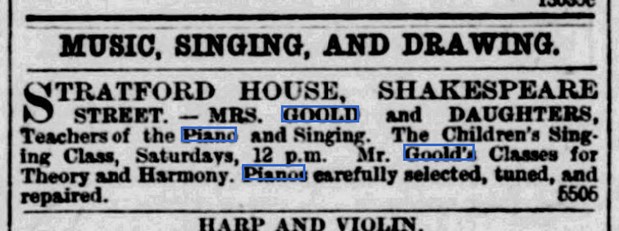

As their family grew up, Clara’s daughters joined her in piano teaching to contribute to the family income. Adverts in Nottingham newspapers from the late 1880s promote “Mrs Goold and daughters” who offer piano tuition and children’s singing classes. Joseph also offered classes in music theory and harmony.

Her daughter Kate married young, to an engineer in the Public Works Department in India who whisked her away to a city in the east of that country, but the rest of the children stayed very much at home. By the time of the 1891 census the whole elder portion of the family were referred to as professors of music – so, though she might have wished to escape the role her musical abilities put her in for her entire childhood, Clara’s talents had brought her full circle and were an important far of the family’s financial structure.

Despite their residence and work in Nottingham, Clara and Joseph and their brood seem to have spent considerable time back at home with his family in Wiltshire. It was here that eldest daughter Daisy had got to know a fellow musician, Herbert Spackman, whose family were very prominent in Corsham. She eventually followed him to New Zealand, and married him in Wellington.

At home in Nottingham, Clara had started to take in resident piano pupils to train as her house gradually emptied, though by 1894 only Joseph was being referred to as a music teacher in business and street directories. Her daughter Kate was widowed in Cuttack, India, in 1892, so returned home to Nottingham with her tiny son, and lived with them and taught piano too. They lived at Stratford House, in the town’s Shakespeare Street, and operated as a family-run music school, with their unmarried daughters coming and going, and adding to their pupil capacity for the next thirty years or so. Clara’s talents, which she passed on in abundance, kept the household solvent and operating well.

Joseph invented a harmonograph around 1901, which was published in a book on harmonic vibration and vibration figures in 1909. This was a twin elliptic pendulum which generated Lissajous curves – a graph of a system of parametric equations. This was his only published research or invention after many years working in harmonics. So, though he was working, the family seems to have relied very much on the solid skills of Clara’s abilities to maintain their livelihood.

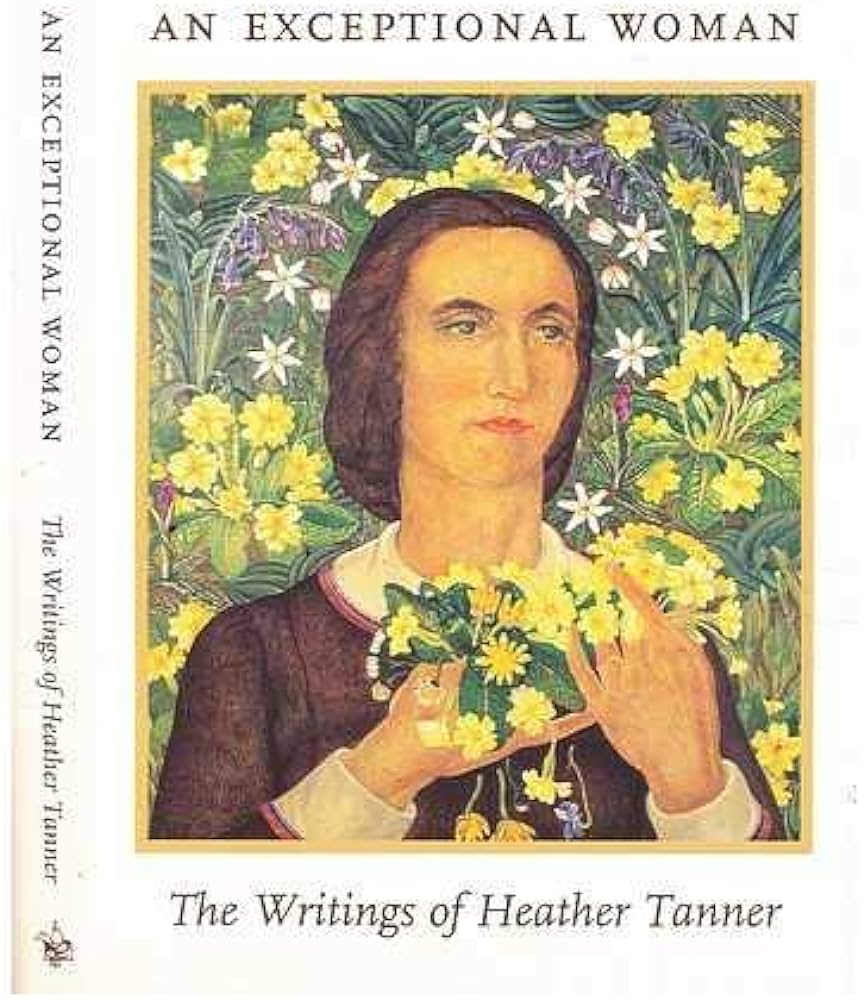

Daughter Kate remarried in 1905, Daisy eventually had three daughters (including Heather Muriel Spackman, who later became Heather Tanner), Irene became a governess and Amy became a school teacher, but Edith and Bertha mostly stayed at home for the duration and taught piano alongside their parents. Son Vivian seemed to swap careers as often as his father did, taking in mechanical engineering and being a nurseryman, but eventually settled on architecture. Her two other sons both took up religion, but while Stanley was a reverend in Nottingham and later Suffolk, Ernest had been a schoolteacher at first but then moved on to the church in South Africa.

A 1905 advert in the Nottingham Guardian promotes Clara and Herbert’s music teaching in piano, singing, organ and harmony, and says that they’re working alongside one of their daughters – though it isn’t specific which, and could have been Alice or Bertha. They also say that they’re a school for the “Virgil Clavier technique”, which was a way of improving piano fingering by practicing silently so as not to disturb the neighbours.

In 1916, Clara’s father died in Bath. John Henry MacFarlane was described as “Bath’s Oldest Musician” in his obituary in the Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, which described some of his teaching methods in the words of his old pupils. He reputedly would rap pupils on the knuckles with a stick if the scales were played wrong or someone sang a flat for a sharp. Although nothing out of the ordinary for music teaching in this era, Clara must also have been subjected to this treatment as a child. It is not known if it was a technique she used herself with her own piano pupils, but it seems likely. The obituary also reveals that Clara had come to be with her father until the end of his life.

Their grandson, son of their daughter Kate, was killed on active service during the First World War. He had been an officer.

Clara and Joseph remained in Nottingham until around 1922/3, when they retired back to Corsham. They celebrated their diamond wedding anniversary at the residence of their son-in-law Herbert Spackman, at Rose Cottage in Priory Street, and the occasion was reported upon in the Wiltshire Times. They appear to have moved in with Daisy and Herbert and their family so they could be taken care of in old age.

Joseph died, aged 90, in Corsham in 1926, and was celebrated in the newspapers as a musician and scientist/inventor. Typically for the time, his obituaries only mention the occupations of his sons and not his daughters, and do not even mention Clara by name – she is just “the widow”.

After Joseph’s death, Clara is known to have lived quietly in Corsham during her retirement and widowhood, occasionally helping out her daughters in their piano teaching.

When Clara died in the summer of 1939, she was given a glowing obituary in both Nottingham and Wiltshire Newspapers. The Nottingham Journal describes her as “one of Nottingham’s foremost pianoforte and singing teachers in pre-war days, and among her pupils were many men and women who have since become famous in the world of music”, but doesn’t actually name any of them. She was remembered as the teacher of piano teacher Alice Hogg, who was well-known in Nottingham at that time.

Her two piano-teacher daughters continued to educate the children of Corsham on keyboards through the 20th century, so her musical legacy is still felt in the town today. But of her remaining grand-children, it is Heather Muriel Spackman, later Heather Tanner, who is the best known – she was a writer and author, and a peace campaigner.